Nick Liu, nearly eighteen, died unexpectedly last week. Nick was born in 2004 in New York, the beloved son of Chen-Hsiung Liu and Wanda Feinberg. Liu and Feinberg moved somewhere very remote and cold when Nick was at the beginning of his adolescence, which is probably why he killed himself.

As a child, Nick was known for his reserved and shy demeanor. The editors of the Bangor Daily News’s Obituary section unanimously agree that he turned into a cunt once he grew out of that phase. Nick loved anything obscure and would deliberately look for works of art, music, and literature that made him look erudite. He wore his idols on his sleeve, most of whom undoubtedly also killed themselves or overdosed. We like to believe that Nick knelt down in front of his torn poster of Ian Curtis and begged to be taken with him. We at the Bangor Daily News think about Nick Liu and all that comes to mind is death. We believe that he was never really living to begin with.

Nick Liu is predeceased by his grandparents, Pei-Hua Liu and Albert Feinberg, as well as his sister, Melody Liu.

My name is Nick Liu and I just wrote another thing about me dying. It’s the fourth one that I’ve written this month, and it’s since been folded into a wad and hidden in my desk.

My name is Nick Liu and this whole “killing yourself” business got old a long time ago, but I’m not sure what to do once I’m over it, because I’ve sort of screwed myself over at this point due to believing I’d be dead all this time. I have maybe a handful of friends, three quarters of whom I hate most of the time, the last quarter being people who probably think I’m really annoying to be around, and they’d be right about that, to be honest. My dad works translating patents and other technical documents from English to Chinese, and my mom works translating them back again. They’re asleep when I’m awake and vice versa.

My room is about what you’d expect. I got blackout curtains a few years ago, but I don’t use them anymore because they make me feel terrible. There’s dust everywhere. Laminated photos tacked to the wall. Pieces of string, fabric, paper, etc., strewn across the floor, on every conceivable surface. Cables. Buried somewhere are pictures of me when I was younger. “Enigmatic almond-shaped eyes” (what my counselor called them) looking away from the camera. Epicanthal folds. Small, fat hands, holding sticks or grasping a book. Certificates of something. Finished second place in an art competition in third grade, first in the next.

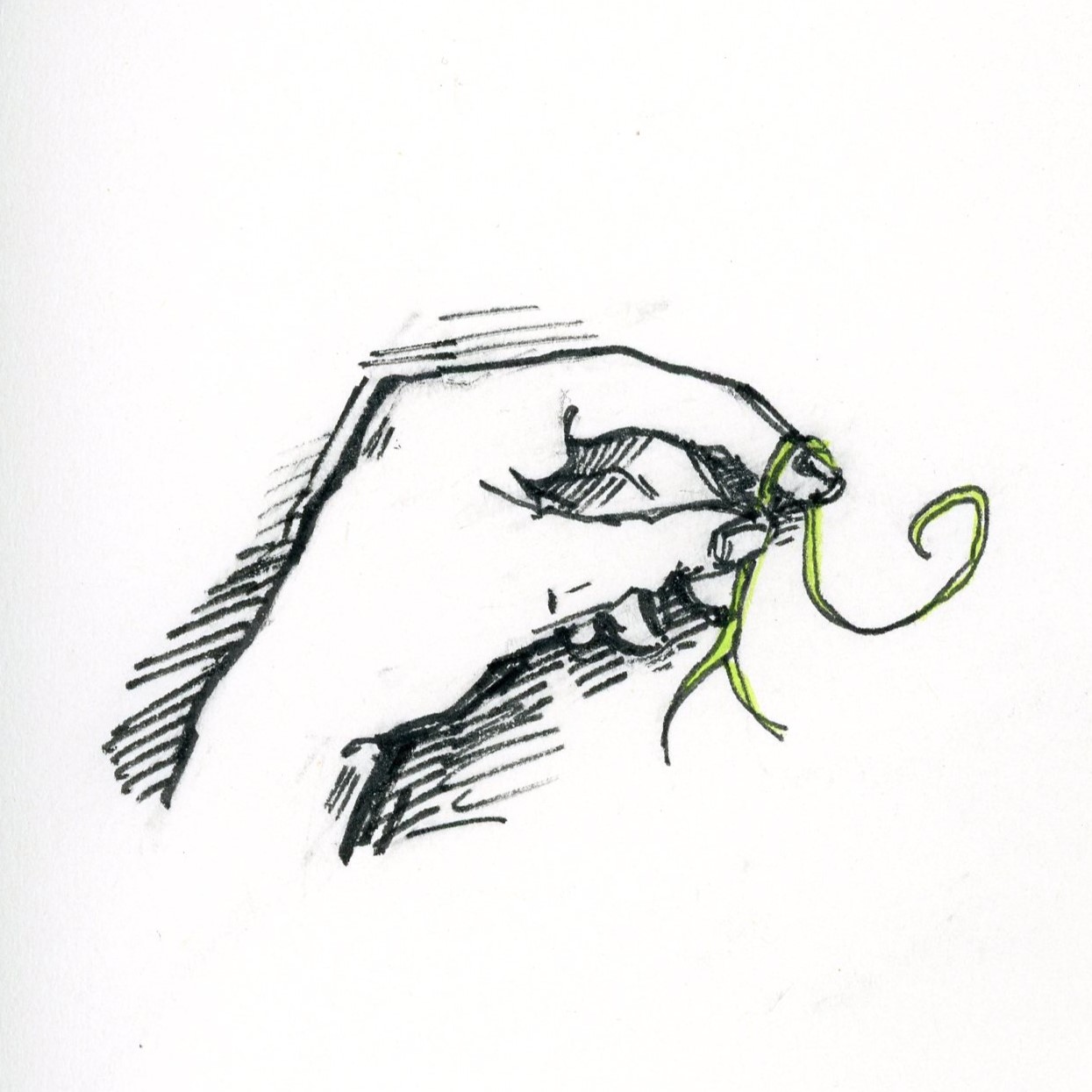

Hairs that don’t match mine (blonde, bleached? greenish?). They turn up everywhere. I know who they’re from, and I keep trying to sweep them away, but the more I clean the more they appear, so I’ve given up.

The place where Nick lives, like many similarly cold and remote places, is slowly shrinking. The average resident of his town is about seventy years old and 200 pounds. The town's population basically halved overnight about thirty years ago, leaving dozens of empty houses untouched since the eighties. When it's not too far below freezing out, too wet, or too windy, Nick spends his time cataloging these houses with his similar-minded friend, Roy. Things have been pretty awkward with Roy since Nick tried to make a pass at him two weeks ago out of loneliness, but Nick's pretty sure that Roy's since forgotten. He doesn't know how he feels about that.

Example A. White, slightly slanted, cube-shaped house. Door is ajar, about a foot or two off the ground. The foundation is exposed. In the entryway, there are embroidered baseball hats ("CARIBOU HISTORICAL SOCIETY 1987," "PELLETIER PLUMBING AND HEATING") and belts hanging from coat hooks. A disemboweled, stiff bird a few feet from the door, splayed on its back.

NICK: (Pointing) Oh, Roy, all the beauty in my life is either sleeping or dead.

ROY: Mnngghh…

Example B. Big, white, sprawling house. Fairly secluded. One of those porches with glass windows in front. Doors are boarded shut. Nick and Roy gingerly step around petrified heaps of deer shit to pick at the relics buried in dust and cardboard on the porch. There's some croquet mallets. A broken mirror. Some naive paintings dated 1991 on the back.

ROY: I think that edible's kicking in.

NICK: Okay.

ROY: Let's go back to my house. Oh, do you think I can punch through one of these windows?

NICK: Please don't.

ROY: I totally could. Hey, check this!

Roy lets out a very primitive-sounding whoop and smashes his fist through the thin glass. Laughing stupidly, he turns around to leave and vaguely gestures for Nick to follow.

ROY: Didn't hurt at all.

NICK: There's… ooh. (Picks Roy's left hand up, quickly puts it down.) There's a little piece…

ROY: No big deal. (He wriggles an embedded piece of glass out of the side of his hand.) Hey, tell me a story.

NICK: Okay.

“Once upon a time, before there were any countries or politics or civilizations, God made two guys for the hell of it. One of them was tall and thin and the other one was short and kind of pudgy. They both looked white, but such racial distinctions didn’t really matter at the time.

For the one who was short and kind of pudgy, God took a little baby lamb from somebody’s flock and put it on a big, celestial pottery wheel. They kneaded it and poked at it while it spun around and around. Eventually, the little lamb had been shaped into something human-like. Its snout was pushed in, ears shortened, its fur smoothed down to become skin. God gave it black, stringy hair fashioned after the wiry branches of midwinter. God opened it up and gave it a heart, lungs, a human brain between its ears, and all the other fixings. Then they sewed it back up and buried it in the earth. All in all, he stood at around five feet and six inches, and looked kind of like a girl, but God intended for him to look like a boy. For all of eternity, the little lamb-boy would resent God and humanity for what they turned him into, but he would never find the words for it, and his creation would remain a distant, muffled memory.

For the one who was tall and thin, God went into the forest and took the carcass of a deer into their arms. God worked around the body, adding layers of muscle and fat and cotton, stretching and pulling as needed. God fashioned its hair out of corn silk and spiderwebs, its thin lips out of red clay, its spleen out of flax fibers, its genitals out of intestinal lining, and so on and so forth. God imbued the stale deer’s heart with new life and refashioned its innards to be functional. Through its blackened veins ran newly hot, newly red blood. They looked at their work and nodded, and then buried him in what’s now known as Västerhaninge, Sweden. For all of eternity, the little deer-carcass-boy would believe that he was dead, even when he clearly appeared to be alive to others. But he’d stay alive until he eventually blew his brains out, eons after his creation…”

ROY: This is getting too complicated for me…

NICK: I’m not even at the good part yet.

Roy’s house is a sloping construction that sits immediately in front of a seventy-five degree drop. In the front, there’s one of those ubiquitous screened porches, the right side of which is covered with a bunch of cardboard boxes. On the left side, a rocking chair. Ahead of it, a mailbox painted with a sunflower and the name “Deschenes.” The house is pretty big, but each section of it seems like it was built without referencing the last, so everything kind of tilts a little. Roy’s dad is in the living room drinking a Coors Light or something in front of the pellet stove. He’s big, bald, and heavyset, sitting on top of a faded Carhartt jacket, wearing glasses with thick, round frames. He says hi to Roy. Roy says hi back. Nick averts his eyes because he’s not yet sure of how racist Roy’s dad is, and it’d be pretty awkward to ask. They climb up the (slanted, too steep) stairs into Roy’s room. Some of the things in there:

It’s late November, which means that it gets dark at around four. Nick shrugs his jacket off and throws it somewhere. Roy collapses onto his bed and Nick climbs over him to look out of Roy’s window. The sunsets up here, he thinks, are always so pretty. Roy and Nick laze around for a minute in what is either comfortable silence or boredom. Outside, Christ, the treelines seem perfectly cut out against a postcard-looking backdrop, light gracing itself through trillions of refracting particles. If it weren’t so beautiful outside, I’d be so much less confused, Nick thinks. I wish this was just a horrible pit of a place. The light makes everything seem more profound. The shining snow. The gleaming potholes. The shimmering inches of black ice over everybody’s driveway. Why am I still sad?

Roy flips over and shoves his phone into Nick’s face. On the screen, there’s a picture of a small kid holding up a cute little drawing of two people holding hands. One of them’s a girl, judging by the triangle-shaped body, and the other’s a boy. On top, there’s the names “RACHEL!!!!!” and “ROY!!!!!” and a big butterfly-shaped thing all drawn in crayon. Roy grins. “Look. It’s my sister. Fucking sick, right?”

Nick smiles. “Heh heh. It looks just like you.”

“Right?” Roy points to his portrait, which is composed of a circle on two big legs with huge, spiky hair. “She even got my hair right.” He then proceeds to throw his phone across the room and lie on his back, limbs stretched out to span the entire bed.

“What was that for?” Nick whines, shoving Roy’s arm back towards him. Roy laughs. “It feels like the air’s giving me a hug!” Nick looks at Roy’s stupid-looking, beaming face and he feels his heart sink. There it is again. That weird, confusing feeling that threatens to close his body in a loop forever. Roy’s chest heaves and he spits out a question. “Nick, you’re an only child, right?”

“Kind of.”

“Kind of?”

“Yeah, I have a sister, but she’s way older than me, so, um… I’m basically an only child. I don’t, like, see her anymore.”

“Ooh, I didn’t know that. You act like an only child.”

“Aww, fuck, what does that even mean?”

Roy swivels his head towards Nick. With very deliberate pronunciation, he says: “It means you’re weird, and you’re sad, and you’re a fucking fairy!” He howls with laughter, and Nick smiles, feeling stupid again. He counts Roy’s teeth, waiting for him to finish. They look pretty smooth. And… straight.

Roy catches his breath. “But it’s okay. I don’t care. It’s, umm, it’s really punk.” And there he goes, laughing again. “Tell me the rest of the story while I fall asleep.”

“I thought you didn’t like it.”

“I never said that. It’s cool. Speak to me, babycakes…”

“Thousands of years after God created those two guys, they rose, infants again, from the dirt. The kids were placed, suddenly, in a strange world where ideas such as government and organized religion existed, and they didn’t even begin to say their first words before they started to implicitly hate the world for it. It was the 1980s in Norway, at the time a very Christian country, when one of them—his name was Øystein Aarseth—picked up guitar and formed a band that played very primitive, very violent death metal, and, umm… hold on…”

ROY: (Muffled) Oh, I fucking get it now. You dickhead.

NICK: No, no, I promise it’ll be cool, I’ve got it all worked out. It only sounds like—

ROY: (Imitating an undefined Scandinavian language) Hurgen, bergen, durgen, bergen… la, la, la…

“Øystein formed this band and he, the bassist, and the drummer were sort of cycling through vocalists at that point. They were looking for one, and suddenly they got sent a demo tape from Sweden. He opened it up, and wow, it stank! And he rifled through it, and he got the tape out as well as a dead mouse that was crucified on this cute little cross. And then…”

ROY: This is getting stupid…

NICK: Aww.

ROY: Does it have to be the Mayhem guys?

NICK: It’s not necessarily the Mayhem guys. It’s just characters with their names.

ROY: Make it, um, better.

NICK: Okay.

“It turned out the person who answered them, who mailed them that demo and that mouse, was another funny little creation of God the way Øystein was. He seemingly rose from the dark earth and didn’t bother to wipe himself off. They soon figured out that their new vocalist was a total wraith of a guy and his inclusion changed the output of the band forever. Before, they were writing these really fat, grinding songs about sawing people in half and fucking their guts. But now, I mean, they had to reckon with this Swedish guy—Pelle Ohlin—and his demeanor, his interests… he could only communicate with Øystein in English for a week or so because they couldn’t really understand each other’s languages. He wrote this stuff that was just like a black pit of icy despair, he’d draw things that were these ugly, angular, schizophrenic-looking compositions, and he’d chase cats around wearing only his underwear… Pelle wrote letters back home to Sweden sometimes, and he’d always complain about how the band was basically living on nothing. They collected welfare money and used it to send tapes abroad. Pelle got money from his dad sometimes for groceries, but he stopped getting it after his dad found out he was just using it to mail people demos. The band didn’t sleep, they barely ate, they drank liquor and Øystein drank Coke and it got to the point where they brought down dust from the ceilings and ashes from burning houses and made bread with it. All they did was rehearse, gig, and hate the world. The whole world was a world full of posers, and the universe was filled to the brim with shit and blood and that kind of thing.

Umm, the thing with Pelle was that he was really kind of insane, but I guess that just helped their image. Well, it wasn’t entirely unfounded. He knew about how he was dead from the beginning, but everyone just thought he was psychotic for saying it. He’d cut himself on stage, during parties, in his room, you know, deep gashes that would reach his arteries, and he’d bleed out all of the blood in his paper-thin body just for it to all be sucked back in. One time he kept cutting himself with pieces of glass while the band was partying, so they just handcuffed him and left him in the corner and then kept on going. And he wouldn’t stop messing around with dead animals. He’d breathe in their scent before gigs so that he’d sound more intense, more necrotic.

At some point he and Øystein moved into this really secluded cabin in the forest, paying the bills with someone else’s money. And they were friends, as much as that could be allowed by their whole situation. I guess it was mutually beneficial in a way. Or maybe mutually harmful. The drummer and bassist would drive out there and they’d rehearse. And I guess Pelle's self-destructiveness helped Øystein with forming his whole front as a comically evil, violent, apathetic guy."

ROY: Snzzz…

NICK: (Patting Roy's back, tucking him into his sheets.) Okay, I'll whisper.

"God made them as a pair, and they weren't brothers in the typical sense but there was some connection there, some subconscious pull between them. They interpreted it as annoyance some days, mutual hatred some others, or sometimes it was friendship, or lust. I mean, when somebody fits your image that well, the only thing you can really do is either kill them or fuck them. They fought a lot, and sometimes Pelle would be afraid to speak while Øystein was in the room or they'd chase each other around with knives or shotguns, but other times they'd carry each other's slumping weight upstairs when they were drunk just so they could, um, have a plausible excuse to touch each other, something they'd forget the next day.

And one day, I guess they both got tired of the whole thing. It was winter now, which to them was great inspiration because it meant everything was quiet and nothing was alive. But it practically sucked because they couldn't afford heat, and it got really frigid out there. You could see your breath really well, even if you were curled up in your bed. So their brains and their bodies kind of slowed down, and what they sought was comfort. It's hard to play guitar, cut yourself, or draw when your fingers are numb. So they fucked. And they fucked, and they fucked, and they kept fucking, barely leaving the house for days, until they felt like nothing really existed except for their own physical feelings, endorphins, soreness, and so on. Everything was simple and within arm's reach that winter. Everything was whole.

But then spring came and everything started moving again. Everything went back to normal. Dirty water dribbled off of new, fresh leaves, collecting onto sludgy pools in the ground made from melted snow. And Øystein was stoic and evil again, and Pelle was erratic and insane again. So one day, after a rehearsal, they fucked for the last time, and Pelle started sobbing about how he wanted to die, how he wanted to be in the ground with all of the dead animals he liked to touch. Øystein, feeling drained from his orgasm, told Pelle that if he still wanted to kill himself after all of this time, then there was nothing that he could do for him at that point. And then he left the house to sleep at a friend's place for a few days, and when he came back, he climbed through the window and saw that Pelle had shot himself in the head. The end."

ROY: Snzzz…

NICK: I'll see you later, buddy.

I haven’t cried for years, maybe not since I was thirteen, fourteen, but I always feel like it these days and it just kills me. I’m walking back from Roy’s house and it must be about nine or ten at night. I have to walk really slow and shine my phone flashlight in front of me because of how much ice there is, and if I fall down I’m basically dead. I’ve always been clumsy. I don’t really go outside too much. Whenever I do, I wake up the next day to weird, undefined bruises on my legs. Scabs on my arms. Christ, aren’t I a fucking evolutionary failure? I think to myself, only half-joking.

There’s this yawning void that’s opened in my chest and it’s swallowed my stomach up entirely, pressing into my jaw and threatening to spill out. I don’t know what the hell is wrong with me. I don’t know why I told Roy the story I told, but the words kept coming out, and I didn’t feel like stopping even when it started getting weird and violent. Nick, Nicky, what’s your problem?

God, it’s so beautiful out, I think, looking at the reflections the scant streetlights make on iced-over asphalt, it’s so beautiful. So beautiful. I see someone’s dim silhouette up ahead, a shape that’s pretty stout and slow-moving, and I get scared for a second, checking my pockets for any illicit goods. I keep trudging along and I eventually find myself side to side with the guy. I look at him and he seems pretty unthreatening now that I see him under the light—he’s short, old, shiny-faced. He beams at me and turns around, pointing in front of him. “If you look back on that road, kid, you’ll see the reddest moon you’ve ever seen.” Then he leaves.

I walk a little more and follow his instructions. He was right. The moon is big. And it’s red. And yeah, it’s redder than any moon I’ve ever seen. And I start walking again just to notice that my face feels wet. I bring my hand to my face but the tears just don’t stop coming.

When I started growing older and growing more erratic as a kid, my dad blamed my mom for all of my bad habits. She was the one who carried the germ. The brain-germ, the little slip-up in chemistry that made me so neurotic. I’d hit my head on the wall, bite holes in my mouth, argue with my teachers, that whole thing. I'd cry for hours on end almost every day. I was maybe eleven when I learned what suicide was and it was the same year that I entered therapy, so forever after, I guess I was the designated fuckup of the Lius. As my sister, Melody, went through high school and graduated, it seemed like I was only growing backwards, like I was regressing.

Melody, you were a caricature from the beginning, even when it came down to your name. “Melody” is such an American-born-Chinese thing to be named, something so pretty and poetic and feminine and easy to pronounce. You were so diligent and so charming. All of your friends would come over, back when we lived in New York and I was really little, and I’d just marvel at how put-together they all looked. Melody in the Honors Society, in internships, in Yearbook, in volleyball, in debate, in the Ivy League. Nick in his room, hitting bruises into the back of his head.

Melody, when you were around, I was always conscious about the several inches I had on you in height, but next to you I felt like nothing and I hated you for it. I filled myself with music and art because they were some of the few things you hadn’t mastered. You’d come home extraordinarily late after school and walk into the kitchen to eat your cold dinner just to see me there, playing Aphex Twin on my speaker. You’d yell at me to turn it down and I’d just turn it up higher.

Melody, when you came home from college for the last time over the holidays, you’d bleached your hair and it had turned an ugly yellow color. Mom and Dad gave you shit for it, telling you that Asian girls look stupid when they’re blonde, but you argued with them. I sided with you and we discussed the best way forward. I went to the drugstore and picked up some neon green hair dye and I helped you dye your hair in the bathroom, leaving streaks of radioactive color all over the sink, the towels, the shower curtains. Then we went to my room, even though it was filled with stacks of drawings and discarded toy pianos, and I played you my favorite songs from the past few months, and you told me they all sounded like shit, and I laughed and I agreed.

Melody, I came out to you after that, and you didn’t even flinch because you already knew I liked boys, you said, from the way I walk. I sputtered and asked you what that even meant but you laughed and you hugged me and I got green hair dye on my white Black Flag t-shirt. Then you told me that your boyfriend at school had dumped you for a tall, WASPy white chick, but it was okay because he was a business major. We laughed for hours.

Melody, when your hair was done and all dried off, you shook it out in my room and dozens of bright green-to-light-yellow strands fell out and onto my floor. It was funny at the time, but I later realized that you were losing hair because you weren’t eating.

Melody, that was the last time we saw each other, because you killed yourself a month after that and then we moved to Maine. And Melody, I don’t know why, but I haven’t been able to cry about it until now, years later. And now the tears won’t stop.

Nick Liu, nearly eighteen years old, lies down in his bed in the middle of the night and watches the minutes increase on his digital clock, seeing it go from 1:53 to 1:54 to 1:55 AM. These are my glory years, he tells himself, my beautiful salad days. He just finished bawling his eyes out and now his throat is sore and his nose is stuffy. Nick doesn’t necessarily feel better than he did before he started crying, but he feels a little emptier, like a pitcher that overflowed and released half of its fluids onto the table, and he supposes that feeling is a little less dangerous than the alternative.

Nick shuffles around in bed, too tired to do anything but too screwed up to sleep. A piece of paper is poking him in the leg. He looks at it and unfolds it. It says “I AM THE CROWN PRINCE OF ALL LOWLY FAGGOTS” on it, written in this spiky, faux-metal looking style with a felt-tip pen. Underneath the header, a self-portrait of him standing on a pile of bodies, raising a spiked club in the air. And then, a wall of text:

MY REIGN OF TERROR

REMAINS UNDEFEATED…

AND HERE I STAND

ANOTHER RUNG BENEATH MY HAND!!

ANOTHER WOUND STRETCHING

ACROSS EACH WRIST

FROM CLENCHED FIST

TO CLENCHED FIST!!!

Nick isn’t really sure what state of mind he was in when he made this drawing, and he studies it with a sort of weary embarrassment. What a glorious, interconnected world we live in, he thinks. One where you may toil in a factory as a child to get your degree in Asia, then toil some more to get your degree in America, then toil some more to settle down with a wife, just to have a kid so Americanized that he spits on all of your hard work by spending his time drawing this garbage. The writing, though, looks pretty cool.

And what about the American dream? Nick supposes he had a shot at it, but he blew it, thinking his sister would fulfill her filial duty, leaving him to relax in his role as a fuckup. But now, Nick thinks, but now… He drifts off to sleep, and his dreams start like this:

MELODY: Nick, what were you trying to tell me back then? What if you knew what was going to happen? Nick, what was that drawing? And what was that story you told your friend? Why all the death? Why all the violence?

NICK: I, um, I like black metal.

Nick Liu, nearly eighteen, died unexpectedly last week. He was born in 2004. He was born in 1999. He was born in

He died in his room, where he slashed his throat with a knife. He died in his dorm,

hanging from the second bunk. Where he died hanging from the railings on top of the staircase. Where he died after he swallowed a bottle of pills and then a bottle of

vodka, and when he

Nick Liu, nearly eighteen, died alone. Died surrounded by family. Died in

the hospital. Died with his roommates. Died with his friends. And he died in his bed, where he then died. Where he then died again. Where he

When his sister killed herself, Nick later found out that she’d texted her friend about it beforehand, saying she was sorry and that she had tried to poison herself with over-the-counter painkillers and alcohol, but it hadn’t worked and now she just felt sick and sluggish. She said that she felt trapped and that she didn’t like school anymore. She said that she felt doomed into a life of subservience, if not to her parents then to society, to the economy, and that she kind of disliked everybody around her, the people she’d previously used to attain social and academic success. She said that things which used to be interesting to her or charming now seemed to blossom into these ugly configurations of wounds that only brought her feelings lower. And then she said that she didn’t eat anymore, she didn’t sleep, she felt nothing. And then she said, “I can still use the bedsheets.” And then she hanged herself.

NICK: A few months after you died, I started getting frustrated because I knew that I couldn’t do it as well. Because you’d already done it before me, and now…

MELODY: You’re sick. You see me again after so long, and this is what you say?

NICK: I’m sorry. I didn’t mean for it to come out like that. You know, Mom and Dad never moved any of your stuff in your room until the time came to pack it all up.

MELODY:

NICK: It’s still in boxes. It’s all in there, all of your stuff. I don’t think anyone’s touched it.

MELODY:

NICK: I don’t think they could stand walking past your room every day, so we moved. I was fine with it. The house was just, um, too filled with ghosts for them or something, I guess.

MELODY: How’s life in Maine?

NICK: It’s, um, cold.

MELODY:

NICK:

MELODY: Do you think of me?

NICK: Yeah. It drives basically everything I do.

MELODY: So it’s useful to you?

NICK: Yeah.

MELODY: You sick fuck.

NICK: You know, the first thing Euronymous did when he found Dead’s corpse was purchase a camera to take photos of it.

MELODY: I never got to learn who those people were.

NICK: It came out wrong. I meant to say…

MELODY:

Sunday morning came and went. By the time I’d opened my eyes, the clock said that it was two in the afternoon. Light streamed through the windows, so bright that it made my eyes hurt and made me feel like I was looking at something obscene. Every part of my body sort of ached. I touched my face and it was wet again.

MELODY: Talk to him.

NICK: What?

I shuffled downstairs and poured myself some lukewarm coffee from the pot. I chugged all of it, grimaced, and wiped my face with the front of my shirt, and then I began my wretched, harrowing journey to Roy’s house, assuming he was there. My head really hurt, possibly due to pressure changes. I guess it had rained or something overnight. A lot of the snow had melted just to refreeze, and the road was this treacherous streak of ice.

MELODY: Do you miss me?

NICK: Um, I—

I hit my boots on the welcome mat to get all the sludge off and knocked on Roy’s door. There was only a fifty percent chance that he’d be in there, since he was generally involved in more social engagements than I’ve ever been in my entire life, but I guess I got lucky because I immediately heard his deep voice yowling “HEY THERE, PILLOWBITER!” from the second floor. I grinned and the pressure in my chest collapsed. He slid the window open and poked his head out and I heard some tinny music (Minutemen? Mission of Burma?) playing from inside his room. “The door’s unlocked already,” he said.

MELODY: You have questionable taste, Nick.

NICK: My pickings up here are pretty slim…

I walked up the stairs to see that Roy was now lying in bed, looking at the ceiling with his hands folded on his stomach. The music was at full volume. “Is this how you spend your weekends?” I asked, fully aware of how hypocritical I was being. Roy didn’t move at all when I entered his room. “I just spent an hour de-icing and digging my dad’s car out,” he groaned at me. “I’m playing Hüsker Dü. It’s from the album New Day Rising.”

I listened to it for a little bit. “I’m not really into this stuff. It sounds too, um, American.”

“You’re American. Anyway, all of Bob Mould’s lyrics make me scream and cry, so you should shut up.”

“It sounds like music for someone’s dad.”

“I told you to shut up. Did you know that both Mould and the drummer, Grant Hart, liked boys?”

“Do you think that’ll make me like it?”

“Yes. Oh, God, listen to this part! Listen to it!” Roy started sing-screaming the following lyrics, clutching an imaginary microphone:

“Then the sun disintegrates between a wall of clouds

I summer where I winter at, no one is allowed there

Do you remember when the first snowfall fell?

When summer barely had a snowball's chance in hell?

Was this your celebrated summer?

Was this your celebrated summer?

Was this…”

And now, I didn’t really know why, but I kept watching Roy’s stupid mop of hair flipping back and forth as he yelled, and I felt that great avalanche of hysteria starting to hit me again. Yeah, I thought to myself, was this my celebrated summer? I didn’t know what the words were really supposed to mean, or if they were even supposed to mean anything at all, but I started feeling them, I guess, like a razor’s edge of emotion stretching decades from Bob Mould to Roy to me. I only listen to music that signifies the absence of something, I thought, and I only think about absence, and I only care about absence. Why do I feel like everything’s coming back for me?

MELODY: Do you miss me?

NICK: I couldn’t tell for a while.

It feels stupid writing about it now, but I guess I was so delirious at that point that it seemed like everyone’s ghost was in that room with me, the ghosts of everything that’s ever been done, everything that hasn’t been done. Was this your celebrated summer? The weight of it all pushed me towards the ground and into Roy’s bed without me thinking about it, and I kind of curled up next to him.

“What are you thinking about right now?” Roy asked me, after the song ended. “I don’t know,” I said. “Um, I guess I’m thinking about how you either die really young if you make extreme music or you live long enough to get fat and ugly.” And the only people I care about are the dead ones.

MELODY: I wish you’d shut up just for once.

NICK: Yeah, me too.

“Yeah, Grant Hart died just a few years ago,” Roy said. That scary, unstable feeling started rising inside of me again. I pushed my head into his back and wrapped my right arm around him, smothering him. Roy froze for a moment. “Hey, it’s alright with me if you do that, just don’t, uh, pop a boner or something, heh heh.” My voice was muffled by his sweatshirt. “I can’t even remember the last time I got an erection, Roy, so don’t worry,” I said. He laughed. “Are you sure that’s healthy?”

MELODY: When’s the last time you felt like I was missing?

NICK: Christ, you can’t just—

I felt my eyes starting to sting and within a few seconds I started to fucking cry. I grabbed Roy tighter so that he wouldn’t be able to turn around and notice, and he made a sort of displeased noise at that, but I guess he didn’t actually care. When I pulled away, I saw that my tears had left some wet spots on his clothes. He shifted uncomfortably. “You okay, dude?” Roy asked, and I shamefully noticed the concern that seemed to color his voice. “Yeah, I’m okay,” I said, wiping the tears and snot from my face before more of it came out.

I felt kind of far away when I spoke again. “I just, um, I miss you.” Damn tears always find a reason to break free.